The number of comparable companies in a TNMM search can vary widely, from as few as five to more than fifty. Smaller sets are naturally more vulnerable to tax authority challenges: the removal or addition of a single company can significantly shift the arm’s length range[1].

The central question is: can we quantify the risk of using small samples? We go beyond the usual qualitative assertions (“it depends on the facts and circumstances”) and provide concrete quantitative insights from a statistical and simulation-based approach.

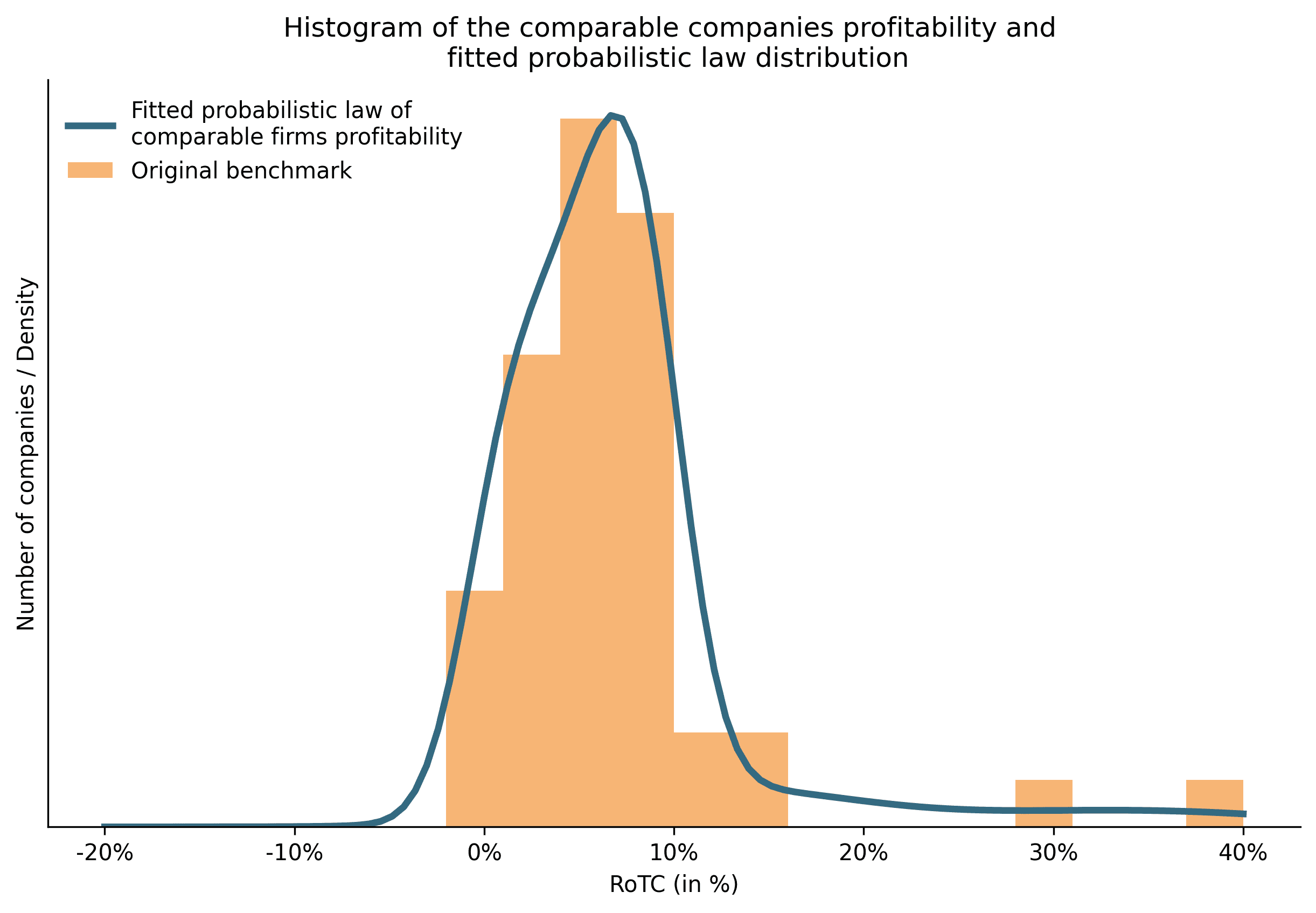

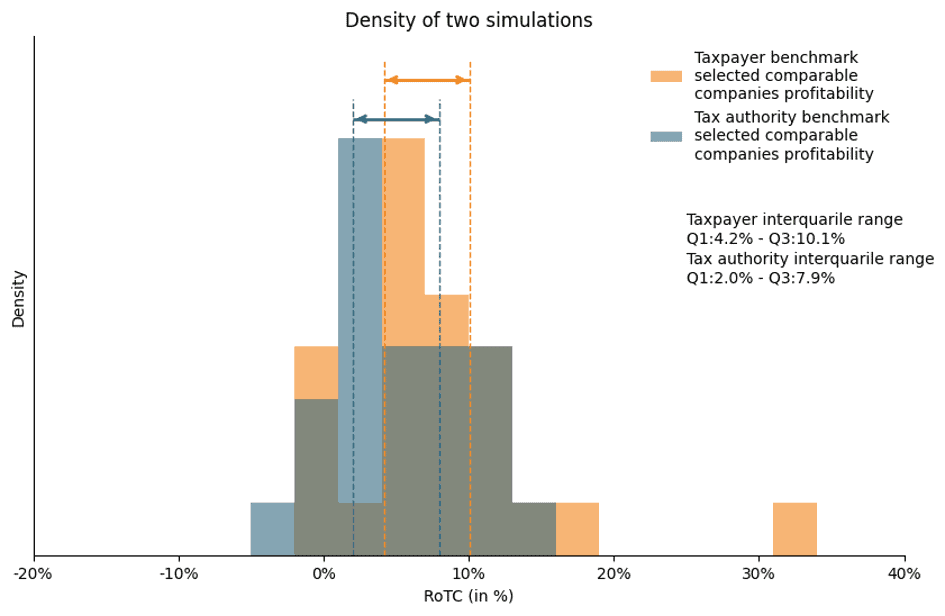

To test this, we modeled a hypothetical scenario where both the taxpayer and the tax authority perform separate TNMM searches, drawing from the same underlying profitability distribution. In this setup, any difference between the two benchmarks is driven purely by sampling variation (i.e. “luck”).

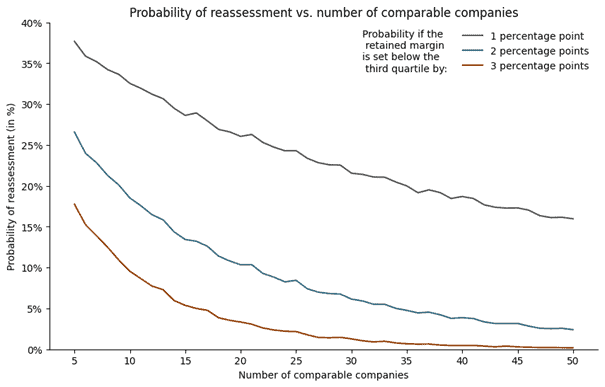

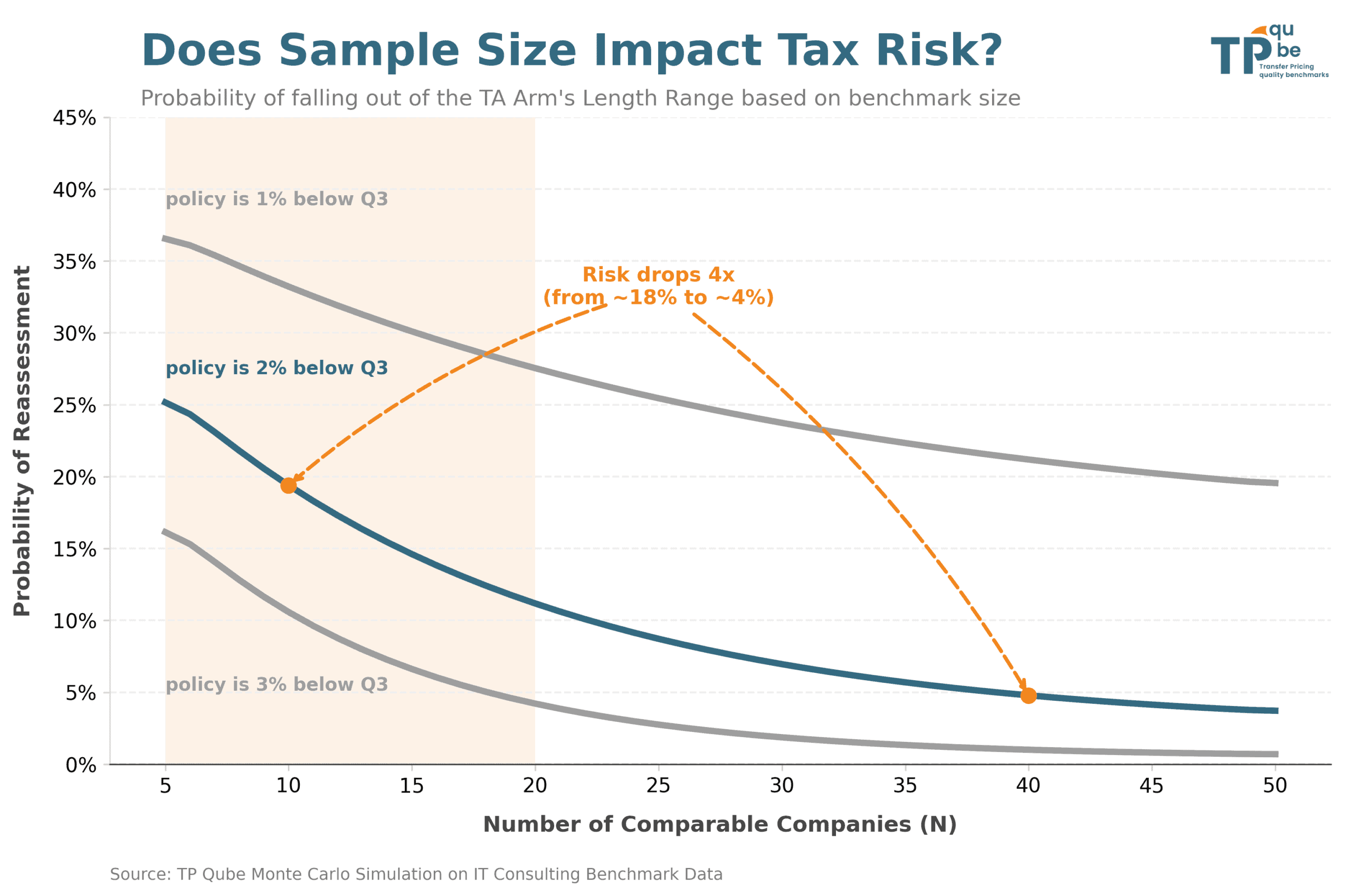

Our findings show that in an IT consulting benchmark, when the tested party’s margin is positioned 2% below the upper quartile, the probability of a reassessment was around 18% for a set of 10 comparable companies). By increasing the sample size, the probability of reassessment drops sharply, at 4% for a set of 40 comparable companies. The main result is best visualized in the last graph.

This article is not a call for larger samples at all costs. As all transfer pricing practitioners know, there is usually a trade-off between the quality and quantity of comparable companies in TNMM searches. But when firms are reasonably comparable, increasing the panel size is always worth considering.