Tp qube

- What is cash pooling?

- What are the benefits of cash pooling for MNEs?

- What financial flows are typically seen in cash pool systems?

- Why are cash pools under the watchful eye of tax authorities?

- Which main factors should I take into account to make sure that my cash pool mimics an arm’s length outcome?

- Ultimately, what are the tax risks associated with cash pools?

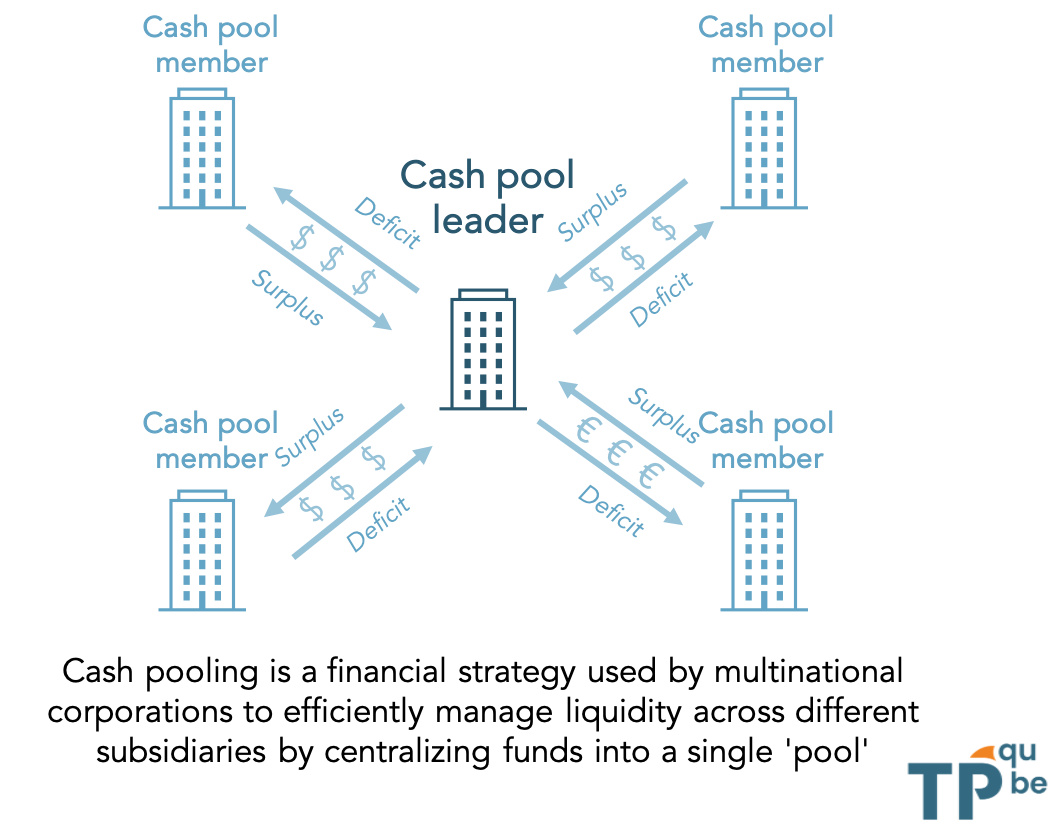

1. What is cash pooling?

2. What are the benefits of cash pooling for MNEs?

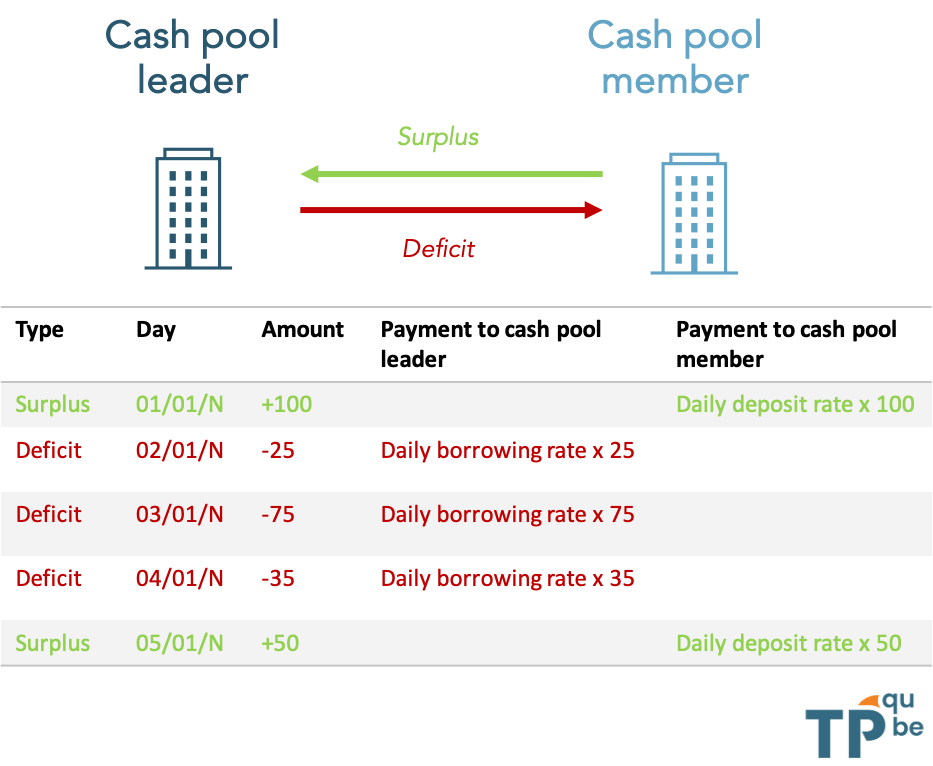

3. What financial flows are typically seen in cash pool systems?

4. Why are cash pools under the watchful eye of tax authorities?

5. Which main factors should I take into account to make sure that my cash pool mimics an arm’s length outcome?

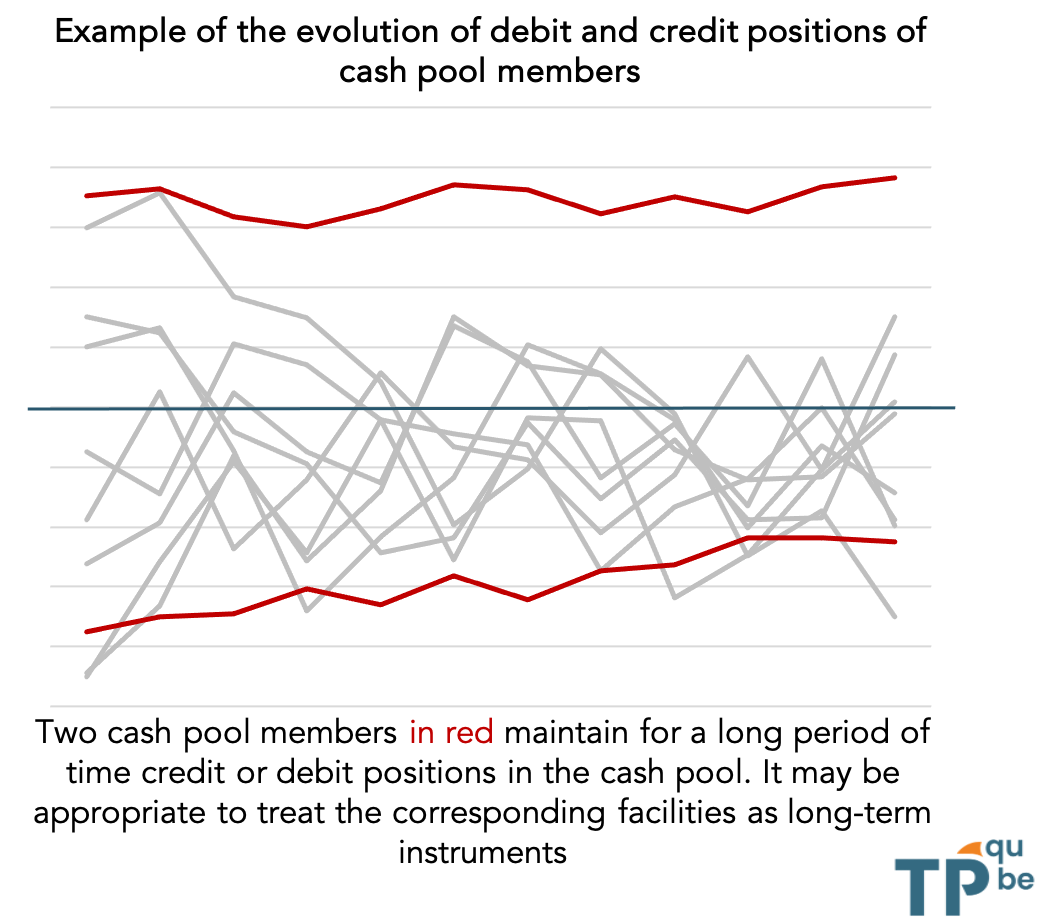

Factor 1 – Identifying long term positions in the cash pool

Factor 2 – Pricing of borrowing and lending interest rates

Quite evidently, borrowing and lending interest rates should be determined by reference to market evidence.

Credit risk is inherent to cash pooling, as some cash pool members may not be in a capacity to repay their debts.

In an ideal setting, all cash pool members would thus need to be attributed a credit rating to capture their differences in credit risks, translating in different borrowing interest rates. This approach is however and not always practical to implement.

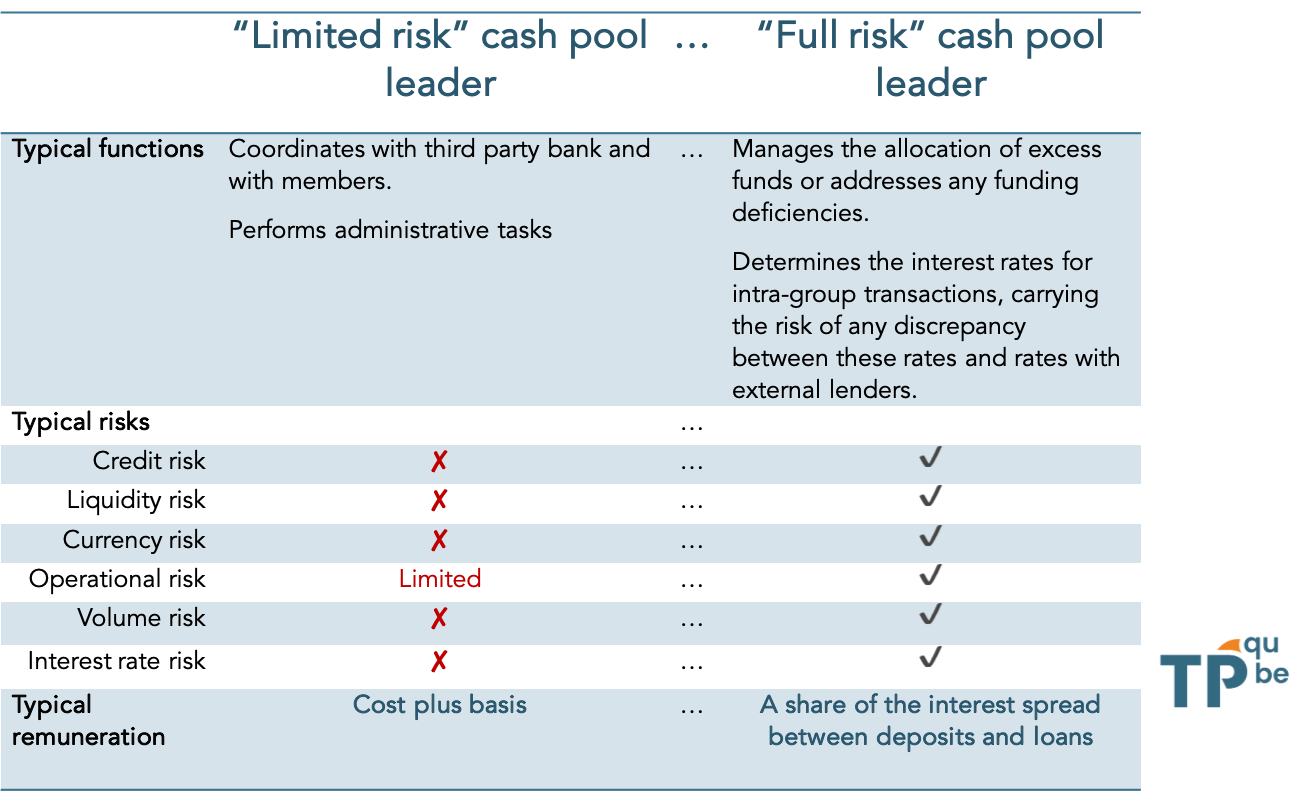

Factor 3 – Remunerating the cash pool leader depending on its functional profile

The remuneration of the cash pool leader will heavily depend on its functional profile. This role can be seen as existing on a spectrum, with its extremes being defined as follows:

Factor 4 – Synergies

Part of the benefit of a cash pool (due to financial opportunities or operational efficiencies – see above) can be considered as arising from group synergies, i.e. incidental benefits attributable solely to its being part of a larger concern. These group synergies should be allocated among cash pool members.

6. Ultimately, what are the tax risks associated with cash pools?

There are typically three main risks associated with cash pools:

- Risks on the level of interest rates. On the borrower side, interest payments may not be fully deductible (for e.g. because tax authorities in the country of the borrower consider that the interest rate is too high). On the lender side, tax administration may add back additional interest payment to taxable income (for e.g. because tax authorities in the country of the lender consider that the interest rate is too low).

- Risks on the reclassification of the cash pool as a long-term loan. The cash pool may be treated as a long term loan by certain tax authorities, notably if the net position of a member does not vary over time. This typically means that tax authorities may consider that the interest rates paid by the borrowing side should be higher (to match the longer maturity of the financial instrument, but also because credit scores tend to be reassessed during the audit). This effect can be particularly large, sometimes increasing interest rates by hundreds of basis points.

- Risks on the reclassification of the cash pool as equity.

These risks concern first the cash pool leader but also any of the cash pool members. With more widespread tax information exchanges, increased pressure on government budget, higher interest rate and intensive usage of datamining tools it should be no surprise that cash pools are now reviewed more systematically by tax authorities.

Notes:

[1] OCDE (2022), OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2022, Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0e655865-en.